Image from CIERAM.

CIERAM and the caravanserais inventory

CIERAM (International Center for the Study of the Ancient Roads) was founded some years ago with the aim of becoming a collaborative research platform bringing together a large number of researchers working on caravanserais. This nonprofit organization was created following the renewed interest in this topic promoted by the UNESCO program on the Silk Roads.

Within this framework, the creation of a general caravanserais inventory was launched in 1998 (http://www.unesco.org/culture/dialogue/eastwest/caravan/fr/page4.htm). This ambitious project, which officially ended in 2004, is now being carried on by CIERAM, involved since the beginning in the UNESCO project, and mainly supported by the EVCAU (Virtual Space for Architectural and Urban Design) team of the National School of Architecture Paris Val de Seine.

Countries in light grey are potentially concerned by the caravanserais inventory project.

The dark grey indicates countries already involved in the inventory.

Image and data processing from CIERAM.

In the beginning covering only eight Central Asian countries and the Medieval period, the project is now broadening both geographically and chronologically, taking into consideration countries extending from the Far East to North Africa and recording stopovers dating from the Ancient period to the Modern era.

The CIERAM inventory now contains 650 references and the organization is at present involved in the elaboration of a GIS of roads and caravanserais. The creation of this tool has two different goals: firstly it will be possible to have at our disposal a dynamic map of roads and caravanserais in order to achieve a better comprehension of their relationship, and secondly using a GIS, combined with other historical and geographical documents and information, allows for the use of new research methods to establish the location of caravanserais which have not yet been geo-referenced (http://www.esrifrance.fr/sig2009/recherche.htm).

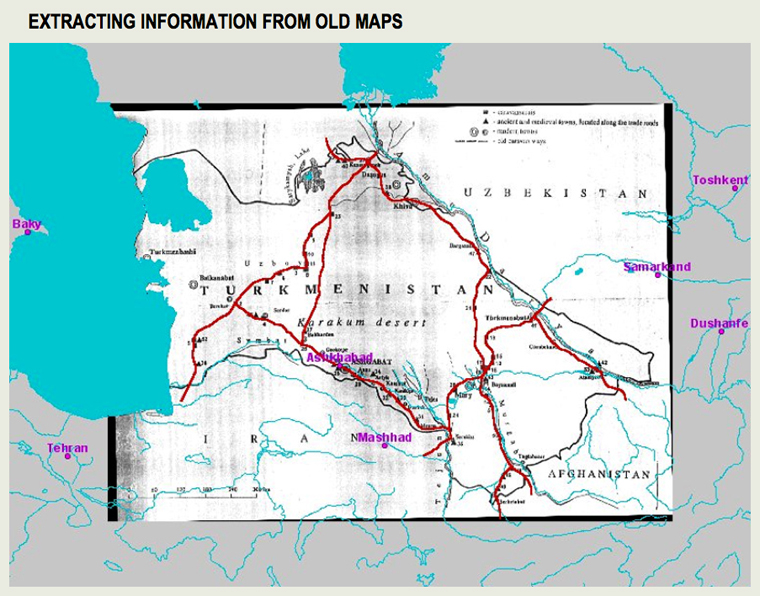

The different steps of the elaboration of a GIS of roads and caravanserais:

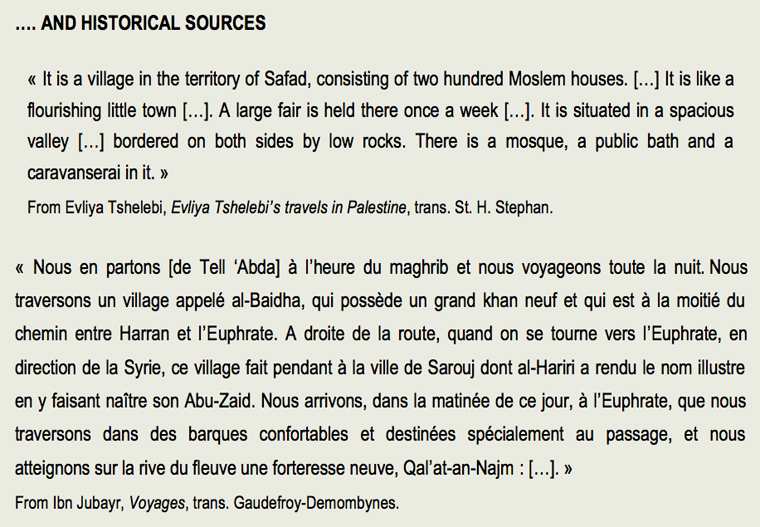

- Collection and processing of the cartographic, iconographic and historic records; digitizing of the old cartographic data.

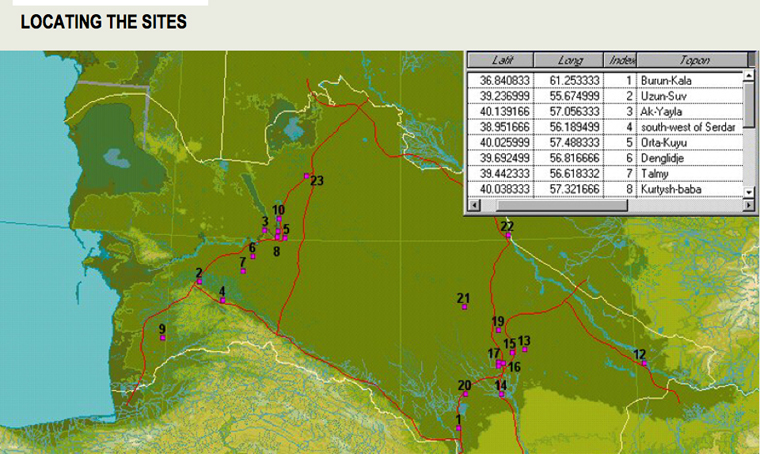

- Georeferencing of the caravanserais and identification of the different itineraries they indicate.

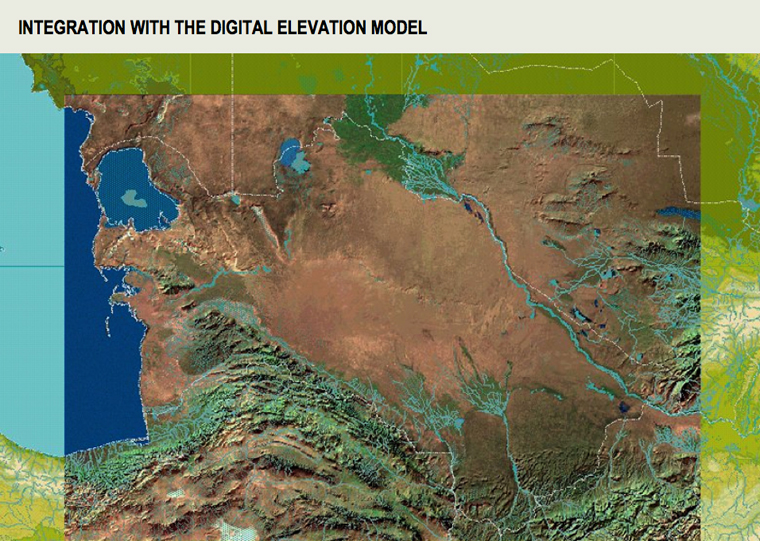

- Transfer and integration of all the data onto digital maps presenting a common geographical reference and integration with the DEM for a better comprehension of the caravanserais' environment.

Data Processing : EVCAU Team. Background paper map: after Pr. Mammedof.

Data Processing : EVCAU Team. Background map : ESRI.

Data Processing : EVCAU Team. Background map : ESRI.

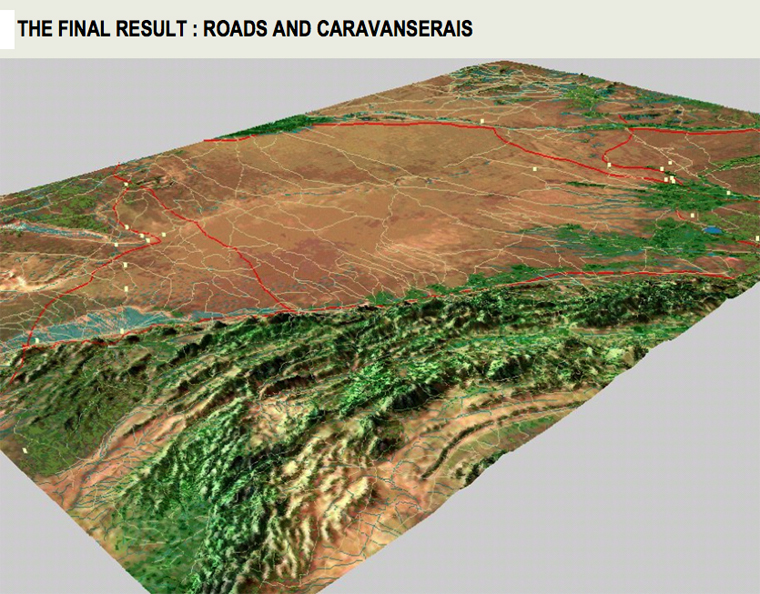

Roads and caravanserais integrated in a GIS. Roads are represented by red lines dotted by caravanserais symbolized by yellow dots. Data Processing : EVCAU Team. Background map : ESRI.

This last step represents the comparison of all the data gathered and should allow the researchers to evaluate the coherence of the different information and their interaction thus permitting different forms of analysis, particularly spatial analysis.

Roads and caravanserais in Medieval Syria

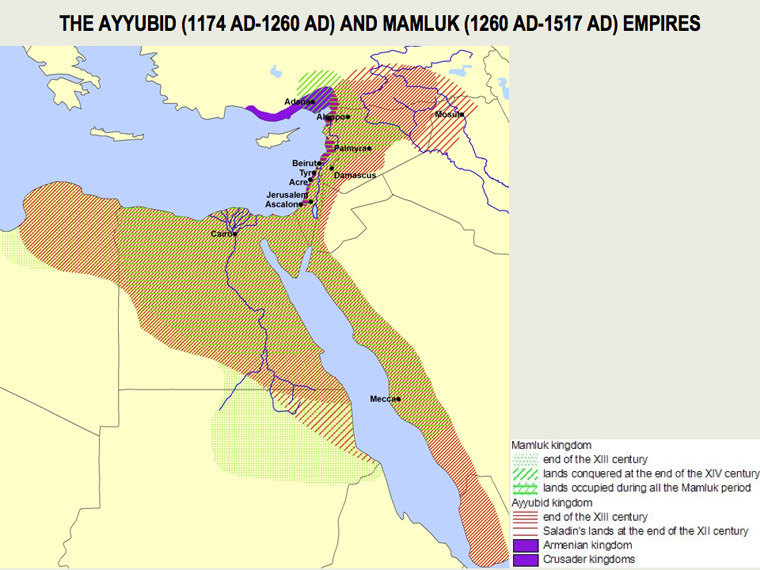

Chronological map of Medieval Bilād al-Šām. Data Processing: EVCAU Team. Background map : ESRI.

The terrain under consideration in this study is the region which, during the Middle Ages, was called Bilād al-Šām by Muslim geographers. Bilād al-Šām included modern Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Jordan and the southern part of Turkey as far as the Taurus Mountains. During the Middle Ages this region underwent important political upheavals. At the end of the XI century, responding to Pope Urban II's appeal, calling for the liberation of the Holy City of Jerusalem, crusaders arriving from Europe occupied part of the country, particularly the Mediterranean coast. Jerusalem remained in the Crusaders' hands for nearly one hundred years. In the second half of the XII century the Ayyubid dynasty, led by Salah al-Dīn, won Jerusalem back and conquered most of the Crusaders' territories. In 1291 AD the Mamluk dynasty, which had taken over Bilād al-Šām thirty years earlier, definitively drove the Crusaders from the whole region.

Aims and Methods

The comprehension of medieval Syrian roads has traditionally relied on the study of historical data, paying relatively little attention to the archaeological evidence, even though represented by wayside caravanserais. These edifices are probably the least elusive proof of the existence of a stopover and, consequently, of a road passing by: they can thus be considered spatial-temporal tags providing fixed and significant points for the reconstruction of the communication axis followed during different periods. The aim of the research is to propose a reconstruction of the medieval Syrian road network supported by both archaeological and historical sources alike.

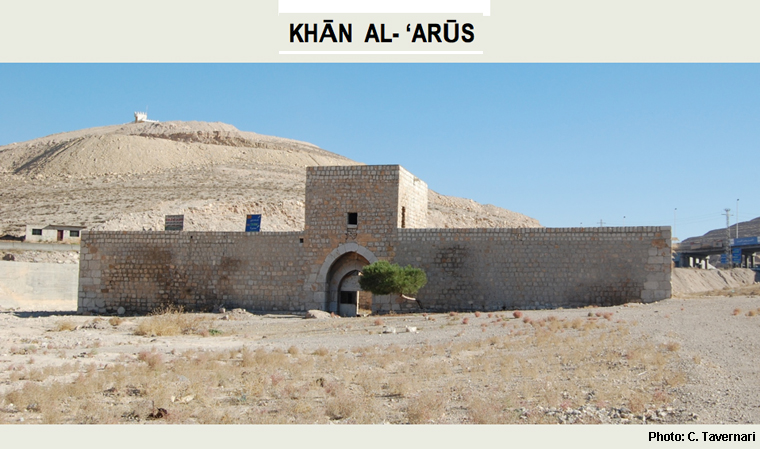

The caravanserai of Khān al-'Arūs, built by Salah al-Dīn in 1181 AD. The building is located at about 45 km north of Damascus.

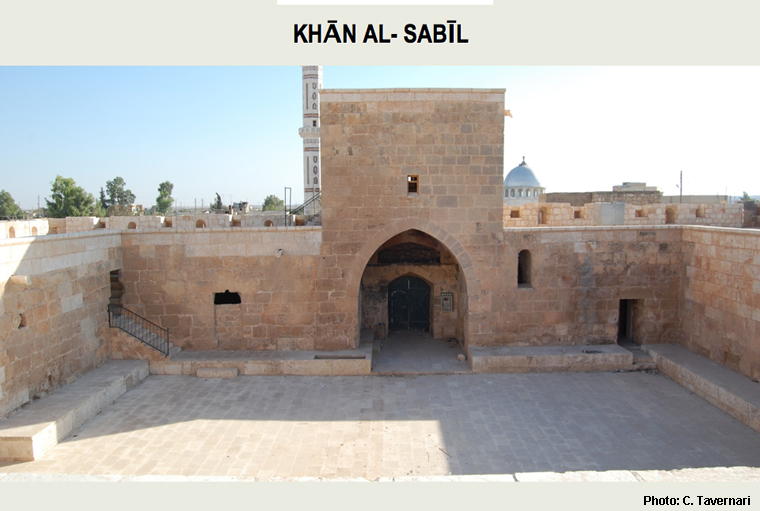

The caravanserai called Khān al-Sabīl. Dating back to the second half of the XIV century it is located on the Aleppo-Damascus axes, about 60 km south of Aleppo.

In order to collect new data on medieval road caravanserais, research has been carried out in Syria since 2004. A first corpus of thirty-three buildings has been established on the basis of the written sources as having been built from the 12th to the beginning of the 16th century The first stage of the fieldwork consisted in a number of surveys in order to get a precise geographical location of the edifices it was possible to identify and fourteen preserved buildings have been detected up to now.

Results of the data analysis

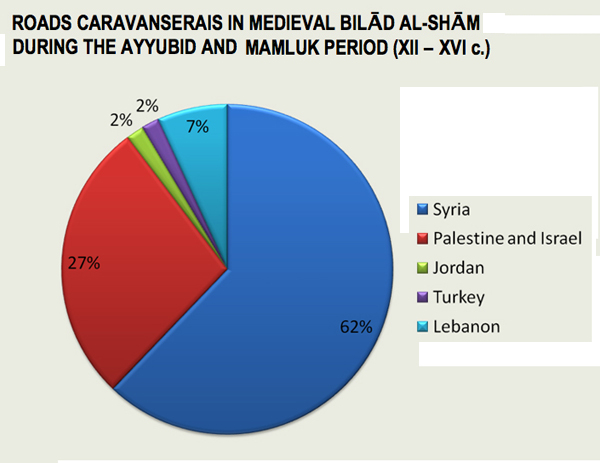

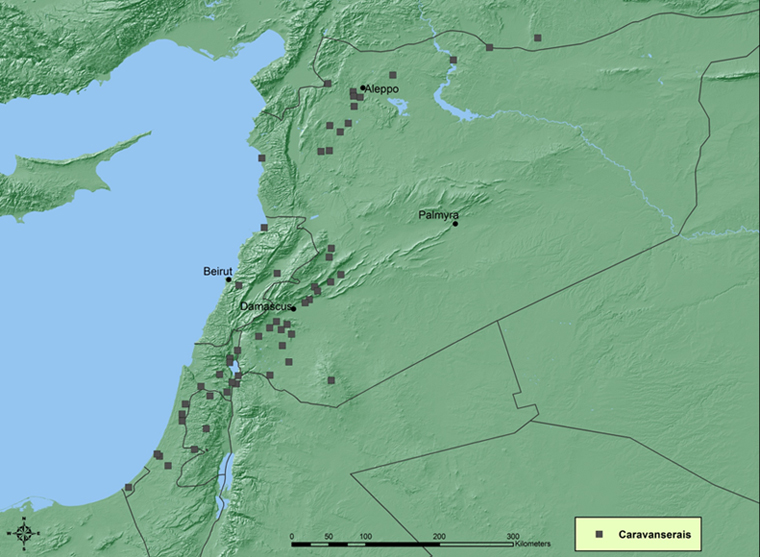

Processing of the data on the caravanserais' location led to the construction of a first map of their distribution in the Bilād al-Šām region.

Two important points should nonetheless be borne in mind regarding the distribution map of caravanserais, even if it does not seem likely that they could heavily influence the present results. In most cases buildings which disappeared did not leave any trace on the ground and their precise position could not be retrieved. On rare occasions, the site itself disappeared or its name changed beyond all recognition and we had to place it on the basis of the descriptions enclosed in the textual sources. Thus some caravanserais could have been misplaced by some kilometers.

It is possible to observe that wayside caravanserais are not equally distributed along the different regional networks, nor is their distribution homogeneous in relation to their date of construction. (e.g. a system regularly expanding).

Caravanserais in Bilād al-Šām during the Ayyubid and Mamluk period (1174-1517AD)

From the combination of these results with historical records and archaeological information some preliminary remarks on the caravanserais' distribution pattern can be made.

- During the Middle Ages caravanserais were apparently not built along Syrian desert roads, apart from rare cases. Some stopovers were built only along the Damascus-Palmyra axes and, even in this case, hardly ever on the first stages of the road, the nearest to Damascus. It is important to note that all the edifices built on this route date back to the Ayyubid period.

- Caravanserais concentrated along the Aleppo-Damascus road during both the Ayyubid and Mamluk period alike. It could thus be considered the most important track of Medieval Syria, at least from the aspect of the caravanserais.

- No caravanserais seem to have been built along the Aleppo-Lattakia road during the Ayyubid and Mamluk period: it was not possible to find any trace in the field or any reference to these edifices in contemporary historical sources. Researchers from the beginning of the XIX century report the existence of ruined caravanserais, but they do not give any date or description of the vestiges. These records were consequently dismissed

- On Palestinian roads all caravanserais appear to date back to the Mamluk period. This situation reflects the history of the region. The Crusaders' arrival at the end of the XI century had probably greatly disrupted the traditional roads which could be freely travelled again only when the Franks had been defeated and definitively driven out of the Holy Land.

In some instances, historical data differs from the situation depicted on the map. According to textual sources the road from Aleppo to Lattakia was heavily travelled during the XIII century and was one of the most important axes for the Venetian commerce with Aleppo, at that time under Ayyubid control. The road is mentioned several times in the commercial treaties between the two states and in 1229 AD the Prince of Alep, al-'Azīz b. al-Zāhir Ghāzī, allowed Venice to build an inn reserved for its merchants in Jisr al-Shughūr, midway between Lattakya and Aleppo (Eddé 1999, 525).

Conclusions

At this stage of the research it is not possible to offer more precise consideration on the patterns, if any existed, of caravanserais distribution and on what causes they depended: political, religious or commercial. Two points that appear important in order to better understand the purposes of a road caravanserai construction should nonetheless be stressed: in the region under consideration, nearly all caravanserais were founded by the most important dignitaries of the military ruling class, powerful emirs and governors and even the sultan himself, and nearly all caravanserais offered lodging free of charge to every traveler.

Occasional Papers (2009-)

Occasional Papers (2009-) Site Visualisations

Site Visualisations