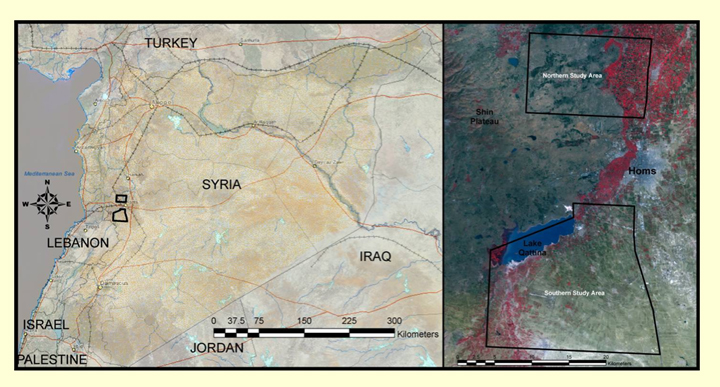

This presentation forms part of a a collaborative British-Syrian project called Settlement and Landscape Development in the Homs Region, Syria, that seeks to compare human activity in adjacent but contrasting landscapes in a typical part of western Syria.

In this case we focus on an upland landscape, where stone architecture is the expectation. In the traditional literature, most discussion of such areas has concentrated upon the evidence for activity of Graeco-Roman date – the Dead Cities of the Limestone Massif on north-western Syria are an excellent example. However, we have very little knowledge of the evidence for earlier periods. This is, we suspect, because we have little idea of what we should be looking for.

The project consists of a Northern and Southern Study Area (NSA and SSA). The SSA is a typical of those settlement landscapes that are dominated by tell sites. However, that part of the NSA located west of the Orontes River consists of a dissected basaltic plateau, wherein stone architecture is the norm.

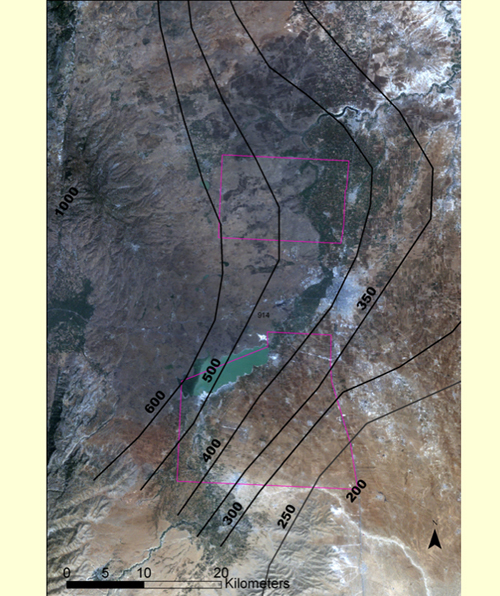

Mean annual precipitation in the basalt zone ranges between 400 and 600 mm. and small stream beds and internal depressions collect winter rain, and can retain water well into spring.

There are numerous agricultural villages there today, so it is by no means a 'marginal' zone. However, the stony landscape represents 'harder work' for farming than the marls to the east, so the area might be described as 'sub-optimal'.

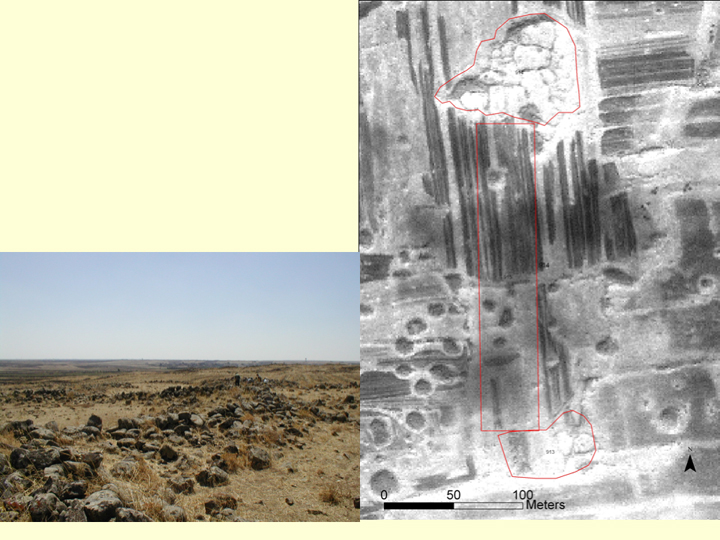

The landscape comprises a series of low boulder-strewn plateaus, interspersed with shallow colluvium-filled valleys and depressions. The surface is littered with basaltic stone which makes the archaeology hard to understand on the ground.

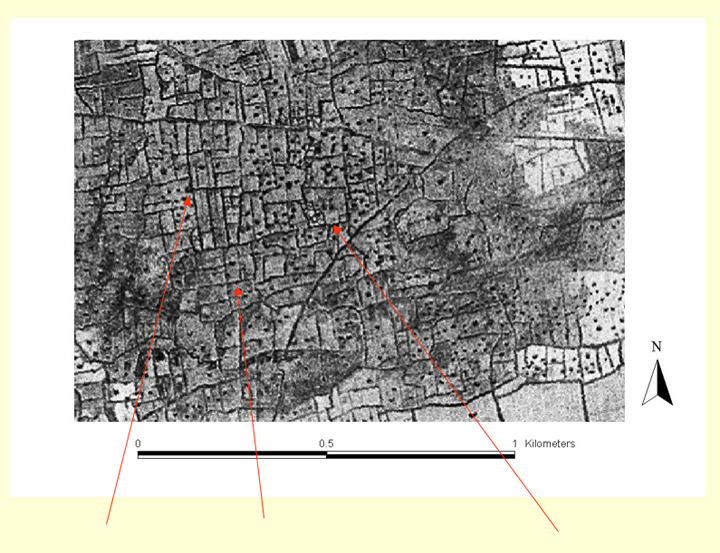

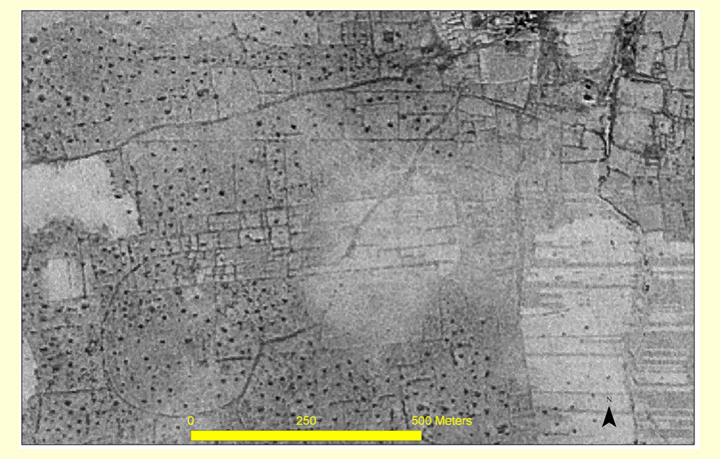

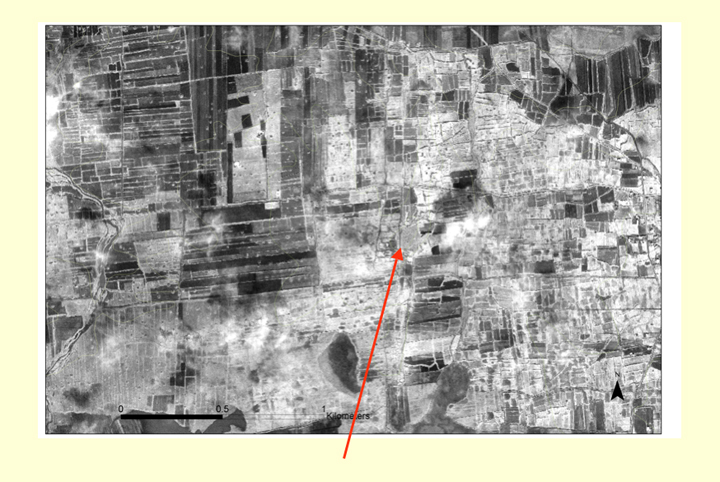

However, high resolution satellite imagery reveals a mass of cairns, field walls and groups of structures. This is a text-book example of a 'palimpsest' landscape.

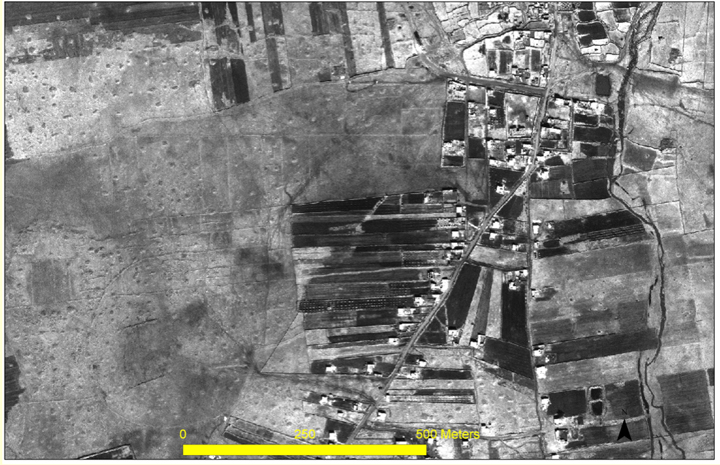

In recent years, a process of de-rocking, designed to increase agricultural productivity, has been destroying the archaeology. The photographs above show the same area in 2002 (top), and in 2005 (bottom). The surface remains have been obliterated.

To understand landscape change we have used a combination of Corona imagery dating to 1969 and Ikonos from 2002. Corona imagery provides a record of the landscape as it existed prior to the recent modification of the archaeology by bulldozing. Ikonos provides contemporary high-resolution coverage with which Corona can be compared. The temporal component of the imagery has been of profound significance for our understanding the impact of human activity on the archaeological resource.

With an approximate spatial resolution of 2 m, Corona imagery provides a lot of detail, with regard to structures.

1m Ikonos Panchromatic provides even more detail but lacks some textural information.

Ikonos multi-spectral data shows texture, but the 4 m spatial resolution is really too coarse for good mapping of features.

Pan-sharpened Ikonos gives a good combination of both detail and texture/colour effects.

The most effective tool, for detection of both pattern and detail in the basalt was pan-sharpened Ikonos data which combines the spatial resolution of the Ikonos panchromatic data with the spectral resolution of the Ikonos MS thus producing a 1m colour product.

This addition of a colour component to the 1 m spatial resolution Ikonos Pan imagery proved especially suitable for the problems of the basalt landscape.

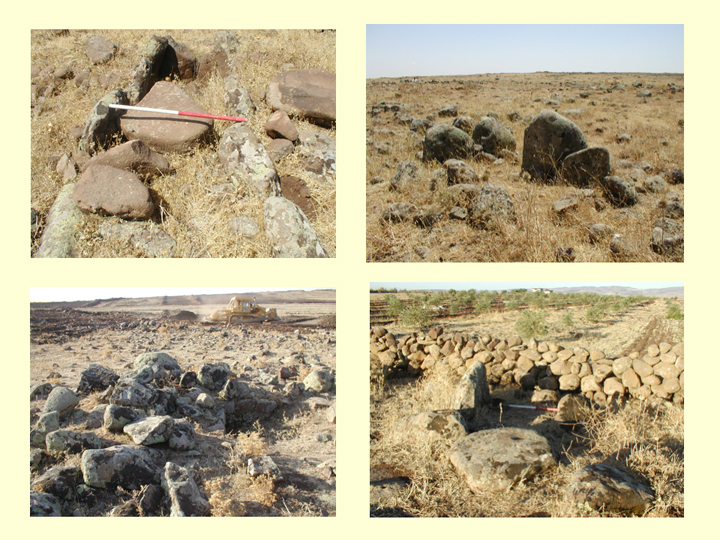

In order comprehend this landscape it is necessary to unscramble the palimpsest of walls, cairns and other structures. Many cairns occur on high points and along ridge-lines. They are less commonly found in the valley bottoms.

Damaged cairns (in photographs above) reveal basalt slabs arranged to form chambers. Most of the cairns are burial structures, not the result of field clearance.

What we initially interpreted as groups of animal enclosures appear, in many cases to represent the remains of settlements.

These sites, as concentrations of rubble, are rarely ploughed, and so often lack the concentrations of surface pottery that usually attract the attention of surveyors. In this rubble-strewn landscape they are generally more readily visible from the air than on the ground.

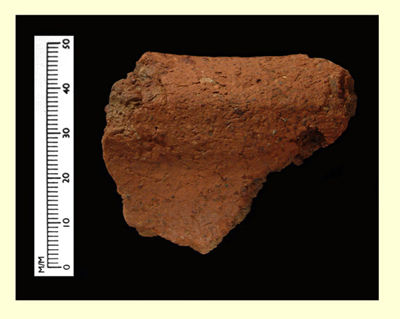

Surface material is generally present in small quantities and consists mainly of small undiagnostic sherds of coarse basalt-tempered pottery, and small pieces of flint, showing signs of extensive re-use.

Perversely the best dating evidence came from a site, part of which had recently been bulldozed. This revealed a ceramic assemblage that could be compared in some respects with the 4th & 3rd millennium BC material from Peter Parr's excavations at Tell Nebi Mend (TNM). Particularly interesting was the fact that rim sherds of the common basalt tempered fabric took the form of holemouth jars. These are not common at TNM, and are generally seen as a form characteristic of the southern Levant.

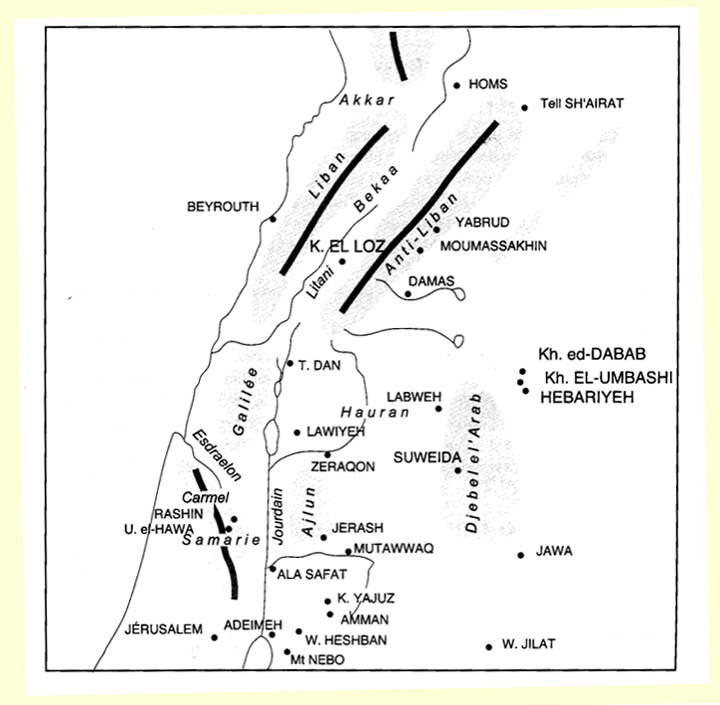

Are these sites unusual or do they constitute part of the 'normal' pre-classical component of upland activity? We suggest the latter, as the evidence from the Homs basalt has structural and ceramic parallels pointing to the Beqa', Southern Syria and Jordan. The map below is suggestive in this respect.

One possibility is that the tombs, circles and settlement clusters, and of course the holemouth jars, might provide indications for the existence of population groups whose 'habitus' differed from that of those living on contemporary tell sites. The basalt has a rich vegetation cover in spring and so may have offered attractive seasonal possibilities to livestock herders.

While the nature of activity in the basalt remains to be explored in the next phase of the project, it clear that the satellite image data has made a significant contribution towards identifying the nature of the pre-classical activity in this 'sub-optimal zone'.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the receipt of financial and logistical support from the following bodies:

- The Directorate General of Antiquities and Museums of Syria

- Council for British Research in the Levant

- Research Fund of the University of Durham

- British Academy

- The local community

Occasional Papers (2009-)

Occasional Papers (2009-) Site Visualisations

Site Visualisations